Post #41: Technology of hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses – I (How it was born, how it spread and why it is in this blog)

(Ref post no. 17, Edible oils: An introduction, for most clarifications that you may need here. Referring to other relevant posts may also be useful).

In the previous post, we saw what technology is and how it grows in dimensions with time. In this post, we will see how ‘hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses’ took birth as science, became a technology and set off in its own special trajectory. There is also a semi-personal history behind my passion for that technology. You will be fascinated, I assure you. I was, when I was young and continue to be when I am not so young.

Why this post? What is it about?

Have you noticed that the only popular product of hydrogenation of oils in India – vanaspati (erstwhile ‘Dalda’) – has been missing from the popular discourse for years? The place it once occupied in Indian cooking, is a story in itself. Some of you may know that the high content of Trans Fatty Acids (TFA) in vanaspati has been the reason for this fade out. Naturally, vanaspati found its way into human body only as food cooked in it and recent research has shown that TFA are more harmful (mainly to the heart) than Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) occurring in all natural oils.

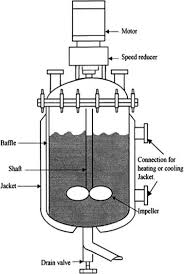

The personal connection: An even more important reason for selecting this chemical technollgy is entirely personal. I have hydrogenated thousands of batches of several mainstream oils during my initial days as a young production supervisor. Those batch reactors (also called autoclaves or converters) were basic, with temperature indication for the reacting mixture and the pressure indication for the ‘head space’ hydrogen as the only instrumentation.

The personal connection: An even more important reason for selecting this chemical technollgy is entirely personal. I have hydrogenated thousands of batches of several mainstream oils during my initial days as a young production supervisor. Those batch reactors (also called autoclaves or converters) were basic, with temperature indication for the reacting mixture and the pressure indication for the ‘head space’ hydrogen as the only instrumentation.

Some times, a setback or a deficiency can be a boon. This need to control the batch thru just two process variables forced me to visualize what was happening inside and if there were any external indicators to that. (“Imagination/creativity is intelligence having fun”. – Albert Einstein). Lack of resources in a constrained but ambitious environment can inspire innovation, sometimes derisively called ‘jugaad’. The utility of today’s ‘start and forget’ process technology in this case is questionable despite the higher ‘rate of production thru enhanced reaction speeds’. But that’s too intricate a point that can be taken up only on the basis of stated demand.

Picking up the thread, hydrogen gas consumption in the reactor was calculated from the fixed volumes of the high pressure storage tanks far away and the line pressure of the gas. When the operator declared, “Saab, yeh batch 200 pound gas kha gaya” (“Sir, this batch has eaten up up 200 pounds of gas”), he meant, “The hydrogen pressure in a specific gas supplying cylinder dropped from the initial 300 psi to 100 psi because of consumption in this batch”. Understanding the language and the body language of the shop floor workman is an art. The varying tin-tin-tin (or, sometimes, even the trrrrrr….) of the valve seat in the vertical-lift NRV at the hydrogenation reactor inlet, the magical ‘hardening’ of the oil, the scary woosh of the cooling water when hydrogenation was over and eventual grainy-oily mass in the tins are memories that have not dimmed over the years.

Picking up the thread, hydrogen gas consumption in the reactor was calculated from the fixed volumes of the high pressure storage tanks far away and the line pressure of the gas. When the operator declared, “Saab, yeh batch 200 pound gas kha gaya” (“Sir, this batch has eaten up up 200 pounds of gas”), he meant, “The hydrogen pressure in a specific gas supplying cylinder dropped from the initial 300 psi to 100 psi because of consumption in this batch”. Understanding the language and the body language of the shop floor workman is an art. The varying tin-tin-tin (or, sometimes, even the trrrrrr….) of the valve seat in the vertical-lift NRV at the hydrogenation reactor inlet, the magical ‘hardening’ of the oil, the scary woosh of the cooling water when hydrogenation was over and eventual grainy-oily mass in the tins are memories that have not dimmed over the years.

Very early in my career, I remember leaning my back against the insulated reactor wall on cold winter nights and early mornings and wondering about the seething, swirling, bubbling mass within, at 200 deg C – transforming itself imperceptibly but really. What could be the temperature pattern from reactor’s central axis to the outer insulation skin touching my back? Also what regulated the loudness and the pattern of the NRV. The ‘realization’ of chemical engineering, food technology and reaction kinetics studied during education, actually connecting with what you saw in real life was fascinating. Today, I would any day recruit youngsters who can do that.

The surviving few reactors even in India today, are better equipped. In the US and Europe, the still operating ones today have Instrumentation and Controls so advanced that the reaction stops automatically when a pre-decided ‘extent and its inevitable trajectory of the reaction’ – fed into a computer at the start – has occurred thru disappearance of a certain quantity of hydrogen into the oil. This quantity of hydrogen is indicated by an in-line Mass Flow Meter (the Coriolis model is preferred) that is controlled elegantly by the ‘state of the batch’. Start and saunter away. The judgment, the observation, working out the correlation between indirect indicators of gas flow rate and the state of the batch…..all swept away by ‘technology’. Is technology washing out imagination and resourcefulness from young lives? Is there some merit in selective, education-oriented ‘back to basics’?

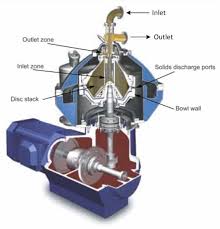

Let’s examine the case of today’s self-cleaning centrifuges for refining oils which ‘run themselves and clean themselves’. The need for higher throughputs has forced enlargement of separator size followed by decrease in spinning speeds and has reduced ‘separating efficiency’. Thus more oil is being lost with soapstock today – anathema for hugely oil-importing Indians.

Let’s examine the case of today’s self-cleaning centrifuges for refining oils which ‘run themselves and clean themselves’. The need for higher throughputs has forced enlargement of separator size followed by decrease in spinning speeds and has reduced ‘separating efficiency’. Thus more oil is being lost with soapstock today – anathema for hugely oil-importing Indians.

At the other extreme was the pathetic-looking batch neutralizer with which I started my career as a boy, which ironically separates with even less efficiency thatn today’s large centrifuges. But the need for smart mixing of the right caustic soda solution into the batch neutralizer at the right temperature, keen observation of developing soap grains sinking semi-spirally, manipulation of agitation, timing of a hot water wash and the delight of a ‘clean’ break between wash water-soapstock-neutralized oil at the bottom were events to cherish for me decades ago. It happened because you made it happen. First the hostel life during education and then this, made a man out of a boy. Only the lucky few get to graduate to higher technology after learning from its simplest avatar.

At the other extreme was the pathetic-looking batch neutralizer with which I started my career as a boy, which ironically separates with even less efficiency thatn today’s large centrifuges. But the need for smart mixing of the right caustic soda solution into the batch neutralizer at the right temperature, keen observation of developing soap grains sinking semi-spirally, manipulation of agitation, timing of a hot water wash and the delight of a ‘clean’ break between wash water-soapstock-neutralized oil at the bottom were events to cherish for me decades ago. It happened because you made it happen. First the hostel life during education and then this, made a man out of a boy. Only the lucky few get to graduate to higher technology after learning from its simplest avatar.

Later came an extensive affair with (tiny by today’s standards) small refining centrifuges. Here the change in the ‘tone’ of neutral oil and the soapstock with any change in process parameters was the point. I remember flitting between refining and washing centrifuges a hundred times, for hours just to watch those changes for minor variations in oil/caustic soda solution/wash water flow rates etc. That’s when I developed the concept of a ‘reagent’ in the caustic soda solution (e.g. a polypeptide as a flocking agent – something that I have not been able to implement to this day) that should improve the ‘break’ and reduce the oil-entrapment in the soapstock. The triumph of ‘high CFM in the soapstock’ and the eventual marginally lower ‘losses’ in refining were the triumph, celebrated somewhat tepidly in dry Gujarat!

The non-personal connection: So is it about nostalgia alone? Nope. Hydrogenation of oils (especially for food applications) is elegant as an oil modification technique, mind-bogglingly complex at many levels as a reaction, intriguing in its ability to be controlled easily and totally externally despite all the complexity of simultaneous parallel and series reactions and a powerhouse of a ‘learning tool’ for chemical engineers and food technologists. Some of such ‘learning’ by me personally has resulted in some interesting ‘innovative possibilities’ concerning hydrogenation of oils. Maybe later.

A few years back, new companies were derisively branded as entities that ‘emerge, merge and then submerge’ alluding to initial excitement around the possibilities of an enterprise, tapering off of excitement, incipient wish to exit and eventual disappearance thru acquisition by a more ‘mature’ business. Ironically, our case – hydrogenation – has parallels to this trajectory but wait. This blog is making a spirited case for continued existence of hydrogenation technology as an impactful educational tool in the area of ‘multiphase reactions’ and even as something that can still be imaginatively exploited commercially.

How hydrogenation of oils was born

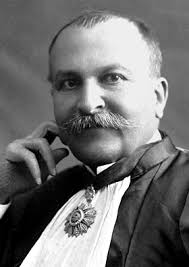

Unsaturated hydrocarbons and oils as hydrogenation reactants: As a result of their research work during 1897-1905, Sabatier and Senderens succeeded in ‘saturating’ unsaturated organic aliphatic hydrocarbons by adding hydrogen in presence of nickel metal as catalyst. (Unsaturated aliphatic double bond + hydrogen, in presence of Ni → saturated bond and hence, compound.) This was essentially conversion of reactive carbon-carbon double bonds (-C=C-) into much less reactive or stable and hence ‘saturated’ single bonds. The double bond is reactive because one of the bonds (the ‘pi’ bond) is spread out in space around the C-C axis, under less attractive or binding influence of the two Carbon nuclei and hence relatively free to join hands with whichever atomic or molecular entity comes along under the right conditions. This ‘joining hands’ with incoming entities is the establishment of new single bonds and the conversion of the double bond into a single or saturated bond. It is this way that ethylene (C2H4) becomes ethane (C2H6) on hydrogenation.

Not surprisingly, the C=C double bond reactivity extends to oxygen and ethylene and under specific conditions, turns into ethylene oxide (C2H4O) which, on addition of water (or chemical hydration), readily becomes ethylene glycol (C2H6O2) – an important industrial ‘intermediate’. Obviously, the double bonds on aliphatic fatty acid chains of oils are similarly reactive and, in their case, their resulting oxidation from any oxygen available in any form causes similar oxides and glycol-type compounds to form. We call such oils stale or rancid – superficially an organoleptic problem but physiologically, a subtle health hazard. One of the main reasons why ‘air frying’ is undesirable (especially with high IV oils) and bought out fried snacks could be harmful.

The unsaturated compounds in Sabatier-Senderens experiments happened to be gaseous lower hydrocarbons – fully miscible with hydrogen (also a gas) – and hence the reaction was, in essence, ‘gas phase, solid-catalysed, hydrogenation’ – homogeneous in terms of reactants. Sabatier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1912 for this pioneering work that has proved to be a major milestone in the annals of synthetic organic chemistry, though it may not be apparent just from ethylene becoming ethane. Important: Sabatier and Senderens’s intimately mixed gaseous mixtures (their molecules jostling against each other) were ready to react when they contacted the catalyst surface at a high temperature.

Victor Grignard Jean-Baptiste Senderens Paul Sabatier

(The Chemistry Nobel that year was shared by Victor Grignard – the legend who created a simple but brilliant reagent – appropriately called the Grignard Reagent – which was polar alkyl/aryl-Mg-halides with electron-dense carbon sites and hence strongly nucleophilic tendencies. The other reactant with electrophilic sites gobbled up the anionic fragments in an addition reaction. Chemistry Nobel has rarely been more ‘reaction centric’ and market-friendly and the Synthetic Organics Industry continues to exploit both the Nobel winning reactions today; it is doubtful if they remember to be grateful!)

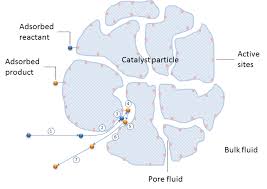

Obviously, unsaturations on fatty acid chains of edible oil (sometimes three in close neighbourhood!) are clones of the unsaturation in Sabatier’s hydrocarbons and hence, in principle, the possibility of hydrogenating oils was immediately apparent. However, oils are high boiling viscous liquids, totally unlike ethylene. In other words, while the double bond sites – the real reactants – are ready to react, they are somewhat ‘dispersed’ parts of larger oil molecules and these ‘circumstances’ make unsaturated oils bad reactants. Not surprisingly, hydrogen solubility in oils is poor or its maximum possible molar concentration in oil (mols/lit) is an additional, inevitable limiting factor for hydrogenation rate.

Physically, the hydrogen-laden oil sneaking thru catalyst particle crevices and contacting the active solid surface sites, is essentially dragging sporadic double bonds with also sparse, tiny hydrogen molecules stumbling along. Chemically, they try to lock on to available active catalyst sites, hoping that they will have enough energy to pass onto the ‘hydrogenated oil’ side. This ‘molecular size and concentration ratio of reactants’ is an interesting, seemingly less explored aspect of hydrogenation of oils. The ultimate insight: hydrogen concentration remains in a narrow range throughout (in most cases) and the double bond concentration ([db], mols/lit) decreases continuously (though not linearly) and hence the ‘concentration ratio’ actually ‘inverts’ during extended hydrogenation. An opportunity, maybe?!

Physically, the hydrogen-laden oil sneaking thru catalyst particle crevices and contacting the active solid surface sites, is essentially dragging sporadic double bonds with also sparse, tiny hydrogen molecules stumbling along. Chemically, they try to lock on to available active catalyst sites, hoping that they will have enough energy to pass onto the ‘hydrogenated oil’ side. This ‘molecular size and concentration ratio of reactants’ is an interesting, seemingly less explored aspect of hydrogenation of oils. The ultimate insight: hydrogen concentration remains in a narrow range throughout (in most cases) and the double bond concentration ([db], mols/lit) decreases continuously (though not linearly) and hence the ‘concentration ratio’ actually ‘inverts’ during extended hydrogenation. An opportunity, maybe?!

Physical and chemical effects of hydrogenation of oils – the TFA: Reconnecting with the original theme, hydrogenation-mediated saturation obviously lowers the IV of oils in direct proportion to hydrogen consumption. This significantly improves the oxidative stability of such oils – the initial selling point of hydrogenation. This outcome is obviously welcome when hydrogenated oils are deployed in high temperature food processing (typically frying or baking) as they turn out ‘fresh smelling and eating goodies’, some distance from being or becoming rancid.

A direct effect of hydrogenation is the straightening of the crooked, rigid natural cis double bonds in original or starting oil, into straighter single bonds and every fatty acid so ‘straightened’ tends to quickly pack closer together on cooling and increase the ‘solid fat content’ of the hydrogenated stock at any temperature. Obviously, the lower the temperature, the more the solid fat content. Also, at any temperature, the higher the extent of hydrogenation, more the packing up. Food technologists quickly began to exploit this as a special functionality of such modified fats to impart firmness to foods containing them and help incorporate air in formulations thru the trapping of air by solidified fats.

A direct effect of hydrogenation is the straightening of the crooked, rigid natural cis double bonds in original or starting oil, into straighter single bonds and every fatty acid so ‘straightened’ tends to quickly pack closer together on cooling and increase the ‘solid fat content’ of the hydrogenated stock at any temperature. Obviously, the lower the temperature, the more the solid fat content. Also, at any temperature, the higher the extent of hydrogenation, more the packing up. Food technologists quickly began to exploit this as a special functionality of such modified fats to impart firmness to foods containing them and help incorporate air in formulations thru the trapping of air by solidified fats.

The other inevitable ‘side effect’ is that some of the original, natural crooked double bonds just flirt with hydrogen and the catalyst site and, find that they don’t have the opportunity or the energy to ‘go the whole distance’ to become saturated. They disengage from the catalyst sites still unsaturated but in a ‘straightened’ form; the crook of the original cis double bond replaced by a slight crick of the straightened (trans) unsaturated bond. This reaction, parallel to hydrogenation, is geometrical isomerization, resulting in the infamous Trans Fatty Acids (TFA). Note how man’s audacity of trying to manipulate the natural crooked double bonds of PUFA and MUFA in oils, resulted in what eventually got discovered as a serious health hazard.

Interestingly and ironically, this TFA formation also raises the solid fat content (though less than in saturation) without any hydrogen consumption. The processors gleefully exploited (when the going was good and solid fat content was the functionality) this by resorting to rampant ‘trans-promoting hydrogenation’. Note: this partially enhanced solid fat content came at a higher IV (because the double bond persisted) but at oxidation resistance that was between that of original cis double bonds and saturated bonds. Vis a vis oxidation resistance, single or saturated bond >> straightened or trans double bond > cis double bond). Until, of course, the sky came crashing down even on moderate TFA content of careful, tarns-inhibiting hydrogenation.

To cut a long story short, the stirred slurry of nickel particles in hot oil bubbling with hydrogenation became the hydrogenation technology – a rare combination of extreme reaction or process complexity and operational simplicity .

How did it spread and where it stands today

Initial versions of hydrogenation of oils started in Europe. America, ‘across the pond’, is good at seeing and seizing opportunities, no? They then had massive cottonseed crops producing sizable quantities of cottonseed oil as a byproduct. They were already using tallow and lard as naturally low IV, oxidation-resisting media for cooking, baking and frying. The possibility of hydrogenating surplus cottonseed oil to a low IV, oxidation resisting cooking medium was interesting and, soon enough, it started in right earnest.

Since this admirable adaptation and adoption in the beginning of last century, millions of tonnes of hydrogenated oils got produced all over the world. Conceivably, they turned into a few billion tonnes of cookies, biscuits, short bread, pie crusts, croissants, pastries, fried goodies delighting billions over generations. Until TFA caught the attention of well-meaning ‘authorities’ as harmful and the fade-out began. Maybe someone will, some day, enlighten us on how many deaths can be attributed to TFA consumption or, what was the contribution of the TFA in mortality. Or, could hydrogenation of edible oils for food applications have been retained in a limited form? Are we throwing the baby out with the bath water? Ummm…Tough one, that.

A thought for food!: were the authorities right in summarily clamping down on hydrogenation or were the processors wrong in meekly abandoning a fascinating modification technique?

Amazingly, hydrogenation for food applications (the focus of our blog), has remained in the ‘hydrogen bubbling thru heated, stirred oil-catalyst slurry in a batch’ format as it enables good control of the quality and extent of hydrogenation. This is central to the quality of the hydrogenated product which will determine the quality of even larger quantities of processed foods in which it is used.

Extensive computerization of the batch operation, a ‘loop reactor’ (essentially still in the batch mode) and some attempts at making the process continuous have been reported, the last, with unexciting results. Interesting as well as intriguing: it has remained practically the same over decades. NI can’t overcome the limitations imposed by nature’s design. Can AI? Doubtful!

Next Post: Technology of hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses – II

Why hydrogenate, how to hydrogenate and what results as product

Visit Disclaimer