Post #42: Technology of hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses – II : Why hydrogenate, how to hydrogenate and what results as product

(It will be useful to keep visiting the previous post for context.)

Why we hydrogenate edible oils

(Note: It must be remembered in all discussions going forward that TFA have made hydrogenation for food applications ‘persona non grata’. The continued discussion is meant to describe an elegant chemical technology which teaches us a lot and which may still have many uses as we will see later).

Since pretty much all organic ‘unsaturation’ in the form of double bonds (not necessarily between C atoms) can be saturated by hydrogenation, hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses is a very small subset of organic modification. Its growth was fueled by:

The improved oxidation resistance of high IV oils makes them suitable for high temperature processing like frying, baking, cooking and for long shelf life expectancy.

The improved oxidation resistance of high IV oils makes them suitable for high temperature processing like frying, baking, cooking and for long shelf life expectancy.

The raised solid content of hydrogenated oils is a functionality exploited in many products: Indian style sweets, margarines and spreads, icing formulations and layering fat in flaky pastries. (Ref the post on physical functionalities of oils).

The raised solid content of hydrogenated oils is a functionality exploited in many products: Indian style sweets, margarines and spreads, icing formulations and layering fat in flaky pastries. (Ref the post on physical functionalities of oils).  The enhanced oxidation resistance in foods processed with hydrogenated stocks seems to favor development of agreeable flavors; the samosa or khasta kachaudi made with them (typically, vanaspati) have a special charm. This applies to desi ghee (anhydrous milk fat) with important differences which we will see in a dedicated post.

The enhanced oxidation resistance in foods processed with hydrogenated stocks seems to favor development of agreeable flavors; the samosa or khasta kachaudi made with them (typically, vanaspati) have a special charm. This applies to desi ghee (anhydrous milk fat) with important differences which we will see in a dedicated post.- Refining of oils has been meant to ‘bring most oils on the same platform of appearance and utility’. Hydrogenation does pretty much the same thing. This offers opportunity to localized soft oils e.g. soybean in the US, Brazil, Argentina.

- High IV soft oils like soybean can be stretched out in a spectrum of products e.g. brush hydrogenated, moderate ∆I for frying, more ∆I for high temperature baking meant to have long shelf/trade channel life etc.

- Many ‘specialty or tailor-made fats’ have been prepared thru hydrogenation but with mixed results. A steep melting fat from forced, hydrogen-abundant hydrogenation of soybean oil (automatically trans-suppressing) can be a cheap coco butter analogue. Fully hydrogenated and fractionated (to remove very low molecular weight triglycerides) coconut or palm kernel oil has been similarly used.

A clear possibility will be described later of producing a CLA (conjugated linoleic acid)-rich oil thru partial, controlled hydrogenation of soybean oil – obviously delivering a proven and valuable nutriceutical in a convenient form. This would be a cooking oil with CLA. We will see this later.

A clear possibility will be described later of producing a CLA (conjugated linoleic acid)-rich oil thru partial, controlled hydrogenation of soybean oil – obviously delivering a proven and valuable nutriceutical in a convenient form. This would be a cooking oil with CLA. We will see this later.

Interestingly, all the utilities are interconnected and only reduction in IV and increase in solidity profile are uniquely defined. In fast, hydrogen-abundant partial hydrogenation, successive (or series) hydrogenation of PUFA to MUFA and even MUFA to SFA dominates. Such ‘distributed’ and ‘indiscriminate’ hydrogenation leaves some PUFA unhydrogenated, if ∆I is moderate. The parallel trans isomerization, happens to a limited extent. This persistence of very low melting PUFA in the hydrogenated stock gives it a somewhat liquid character and limited oxidation resistance.

Such stocks have low solid fat content at close to room temperature and it picks up quickly as temperature reduces i.e. it solidifies fast. Conversely, its solid form at say, 5 deg C (which does have liquid trapped in the crystal matrix), quickly ‘breaks down’ to release a lot of liquid – the phenomenon of quick-melting. This mimics the quick-melting profile of natural cocoa butter. The inevitable TFA in such a ‘cocoa butter equivalent’ is not a dampener because it cannot replace cocoa butter in ‘real chocolate’ at more than 5% by law. This obviously lowers the cost of cocoa butter and hence the moulded chocolate as a whole.

Careful, hydrogen-deprived (managed low hydrogen level in the reaction mixture) hydrogenation eliminates PUFA preferentially before MUFA hydrogenation picks up – a tough call given the need to sustain hydrogenation of PUFA whose already low ‘concentration’ is reducing fast. This guided process is a lot more demanding than an unrestrained process. Hydrogenation takes more time for the same ∆I but the low levels of PUFA make it more oxidation resistant and gives it high solid content at comparable temperatures. You can’t have everything.

Obviously, these two hydrogenation techniques represent extremes in the rates of IV reduction and trans isomerization. These two and all the variations in between represent ‘hydrogenation trajectories’ which determine the hydrogenated product composition or quality and hence utility.

Understanding the hydrogenated oil as a product: This is important both as an ingredient or processing aid that will determine the quality of food products on the market shelves that will be consumed by billions. In other words, what the given extent of hydrogenation did to the original natural oil thru its ‘trajectory’, must be understood. Here’s an overview of the properties of hydrogenated stocks that determine their utility.

(i) The extent of hydrogenation as reflected in IV reduction (∆I): Treating the average IV of soybean oil as 130, it can be lowered just nominally thru ‘brush hydrogention’ (to, say, 120) or all the way to zero IV or anywhere in between. Each stock will have oxidation resistance and ‘solid fat content at any temperature’ that will increase with ∆I. Note: at zero or near-zero IV, all unsaturation (crooked as in natural oils or straightened as formed by isomerization) will have been bulldozed into saturation giving a solid product without any TFA but its high melting point will make it unsuitable for direct human consumption.

(i) The extent of hydrogenation as reflected in IV reduction (∆I): Treating the average IV of soybean oil as 130, it can be lowered just nominally thru ‘brush hydrogention’ (to, say, 120) or all the way to zero IV or anywhere in between. Each stock will have oxidation resistance and ‘solid fat content at any temperature’ that will increase with ∆I. Note: at zero or near-zero IV, all unsaturation (crooked as in natural oils or straightened as formed by isomerization) will have been bulldozed into saturation giving a solid product without any TFA but its high melting point will make it unsuitable for direct human consumption.

Obviously, extensive hydrogenation of a high IV oil like soybean (low final IV) is a way of producing low trans oil. In trans promoting hydrogenation, the rate of TFA formation has to rise initially, equalize with their hydrogenation (the [tdb] maxima) and then the hydrogenation rate has to dominate to gradually taper off [tdb] to zero in full hydrogenation. Thus very low IV sobbean oil can be blended with unhydrogenated high IV oil to produce an oxidation resisting oil with possibly acceptable TFA and with MUFA and even some PUFA.

(ii) TFA content: In the ‘middle-of-the-road hydrogenation’ that is neither trans promoting nor suppressing, both TFA and SFA will be significant. In all three cases, the physical and chemical properties will vary. As a general rule, the TFA will raise oxidation resistance and solid fat content at higher IV.

(iii) Other isomers: Inconsequential for all practical purposes.

(iv) The free fatty acid (ffa) content: At temperatures of hydrogenation (sometimes 200 deg C or even higher) slightly wet hydrogen can cause limited splitting of even dried oils to release ffa, especially for high ∆I which will lengthen the process cycle. This can be limited at hydrogen production and storage level and at product usage level by refining.

(v) Miscellaneous: Lingering Nickel content that slipped filtration of catalyst laden hydrogenated oil, colour (usually noticeably reduced), a certain ‘hydrogenation flavor’ etc. are non-issues that the industry easily addresses.

Thus a hydrogenated stock with a given reduced IV (I = Io – ∆I) and TFA content, practically free of ffa and Nickel is the product that processors aim at and, having verified it thru lab analysis deploy it for food formulation.

But how to make it happen totally externally while the batch is being hydrogenated within a reactor whose inside you have no access to? A million dollar question that was answered by a flurry of research activity in last century (mostly in the US) aimed at relating individual process parameters with how the reaction proceeds vis a vis ∆I increase (or instantaneous, intermediate IV’s) and TFA development up to the intended final IV.

The dependence of product quality on process conditions

That the trajectory of a ‘reaction process’ determines the final reaction mixture composition when parallel and series reactions happen simultaneously has been known forever. But hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses is a special case because, for hydrogenation of a specific oil to a planned final IV,

(i) The physically homogeneous filtrate of the post-hydrogenation catalyst-separating step is the commercial product as a whole, unlike chemical final reaction mixtures which often have to be fractionated to get desired product(s). This is because the actual reactant is those specific sites on parts of the molecules of physically homogeneous oil. These sites change to impart functionalities to the hydrogenated product keeping the whole molecules practically the same. One of the interesting exceptions is fully hydrogenated coconut oil and palm kernel oil which have to be physically fractionated to obtain coco butter analogues.

(ii) the physico-chemical character of this ‘as a whole’ product will have TFA and PUFA-MUFA-SFA content according to process conditions for given ∆I (= Io – I) giving the product its designated utility.

(iii) in the current times of extreme competition and health consciousness, careful control of process parameters consistently leading to a desired product is important for commercial survival which advances in process controls have made possible.

The process conditions that determine the product quality

Just listing them here serves the purpose of lucidity better:

- The reaction temperature: The reaction is highly exothermic and the heat release is initially allowed to raise the temperature of the reaction mixture to exploit the temperature-dependence of the reaction rate. This temperature rise is directly proportional to ∆I and extent of TFA formation; the former more exothermic. This ‘initially rising and eventual constant temperature’ protocol for the conduct of the reaction has been pretty sacrosanct across geographies over time. Point to note: the energetics factor in the rate equation is exploited to arrest the rate slide because of the concentration factor.

The reaction cycle length for given ∆I and the trajectory and hence the product quality are strong functions of this temperature program. For a clean oil and controlled reaction conditions, the intermediate product quality at all stages are pretty much the same across batches barring nominal accentricity because of inevitable poisoning. The actual mechanisms of temperature-dependence of trajectories are intricate but the limited but direct effect on the possible [Hyd], mol/lit cannot be ignored. Initially, at high [db] in high IV oils, the high rate cannot be sustained by even improved [Hyd]) and trans formation will be significant. This has been called’hydrogen starvation’.

- The headspace hydrogen pressure: It essentially increases the hydrogen solubility in oil (in broad compliance of Henry’s Law) and this increased [Hyd] helps the reaction as expected. The increased possibility of oil hydrolysis during hydrogenation at higher pressure is a negative.

-

Catalyst type and usage in kgs catalyst per MT oil: Catalyst making is an esoteric art (and obviously, a science) practised by just a few worldwide and Nickel catalyst for hydrogenation for food uses is no exception. (In his book ‘Chemical Reaction Engineering’ studied by generations of chemical engineers, Octave Levenspiel admiringly calls catalyst-makers ‘magicians!). The type-usage level combination has a sizable effect on product quality. This parameter is obviously out of the process control purview, being entirely in processor’s hands at the start. Obviously, the Nickel content of the catalyst is the operative factor hence, it is customary to specify ‘nickel level per MT oil’. This becomes redundant when a processor consistently uses the same catalyst from the same supplier.

Catalyst type and usage in kgs catalyst per MT oil: Catalyst making is an esoteric art (and obviously, a science) practised by just a few worldwide and Nickel catalyst for hydrogenation for food uses is no exception. (In his book ‘Chemical Reaction Engineering’ studied by generations of chemical engineers, Octave Levenspiel admiringly calls catalyst-makers ‘magicians!). The type-usage level combination has a sizable effect on product quality. This parameter is obviously out of the process control purview, being entirely in processor’s hands at the start. Obviously, the Nickel content of the catalyst is the operative factor hence, it is customary to specify ‘nickel level per MT oil’. This becomes redundant when a processor consistently uses the same catalyst from the same supplier. - Agitation intensity: Up to a limit, agitation increases hydrogenation rate.

- The oil cleanness: Presence of catalyst poisons (gums and sulphur compounds) in the oil being hydrogenated can seriously derail hydrogenation rate as well as quality. Interestingly, hydrogenation with poisoned catalyst was a technique to produce some ‘specialty fats’! See why hydrogenation fascinates?!

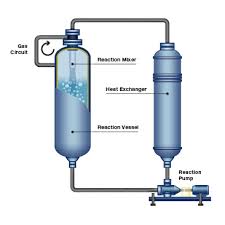

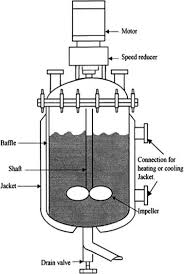

Reactor type: Apart from the conventional, ‘staid’ batch reactor, a ‘loop’ reactor circulating oil from the bottom of the reactor to the top, has been successful, if a bit expensive. The cooling, during as well as at the end of hydrogenation is thru heat exchange with circulating oil. At the top of the reactor, a ‘venturi’ device sucks in head space hydrogen and the hydrogen-laden oil mixes with the bulk reaction mixture. The developing head space gas pressure is thus toned down as hydrogen reacts in the following three ways:

Reactor type: Apart from the conventional, ‘staid’ batch reactor, a ‘loop’ reactor circulating oil from the bottom of the reactor to the top, has been successful, if a bit expensive. The cooling, during as well as at the end of hydrogenation is thru heat exchange with circulating oil. At the top of the reactor, a ‘venturi’ device sucks in head space hydrogen and the hydrogen-laden oil mixes with the bulk reaction mixture. The developing head space gas pressure is thus toned down as hydrogen reacts in the following three ways:

– during bubble rise and continuous ramping up of [Hyd] to compensate for the hydrogen consumption thru diffusion into the reaction mixture

– during forced fine dispersion into oil in the venturi and

– at the liquid oil-headspace hydrogen circular interface at the beginning of the head space.

Relatively recently, a highly automated very high rate reactor (fully computer-automated) has become popular in the west. Feel free to ask for its process analysis which is fascinating.

Next Post:

Technology of hydrogenation of edible oils for food uses – III

Evolution of hydrogenation technology

Visit Disclaimer