Some compelling cases for food processing : Part II, A brief history of milk processing in India and dried dairy wheys

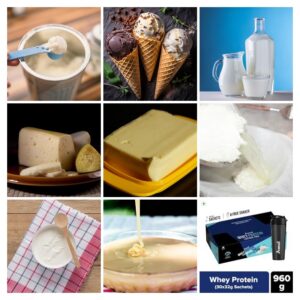

Milk has always had the image of a near-complete food which obviously rubs off on its products – plain, fermented, fractionated, sweet. Hence its processing – whether to make products from it or simply to preserve it for future convenient use – has inherent merit. Here we talk about dried dairy wheys – also called whey powder – as the first among three dried industrial milk products which have all the attributes of milk and more. But to see why it is a compelling case for processing, a brief overview of the history of dairy industry in India will be useful.

Milk has always had the image of a near-complete food which obviously rubs off on its products – plain, fermented, fractionated, sweet. Hence its processing – whether to make products from it or simply to preserve it for future convenient use – has inherent merit. Here we talk about dried dairy wheys – also called whey powder – as the first among three dried industrial milk products which have all the attributes of milk and more. But to see why it is a compelling case for processing, a brief overview of the history of dairy industry in India will be useful.

A brief history of milk and its processing in India: If milk production increases, it obviously mandates an increase in its processing, delivering a mind-boggling array of large quantities of products. Among the products, dried milks and wheys deserve special discussion as less known cases with great potential.

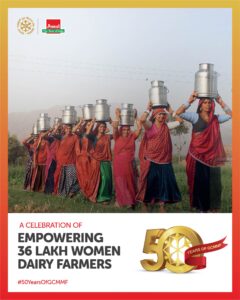

Organization of milk-producing co-operatives in Gujarat (Kheda or Kaira District to be precise) over 6 decades ago has turned out to be a landmark event that has increased milk production by leaps and bounds. This has inevitably set off a cascade of major economic, social and political developments that has changed millions of lives on the supply side and a billion lives on the demand side. Production and processing of milk remains largely in the cooperative sector despite some smaller success stories in the private sector.

Organization of milk-producing co-operatives in Gujarat (Kheda or Kaira District to be precise) over 6 decades ago has turned out to be a landmark event that has increased milk production by leaps and bounds. This has inevitably set off a cascade of major economic, social and political developments that has changed millions of lives on the supply side and a billion lives on the demand side. Production and processing of milk remains largely in the cooperative sector despite some smaller success stories in the private sector.

A brief history of milk co-operatives in India: For over a decade after independence, India imported massive tonnages of milk powder and butter oil (milk fat to raise the fat content of reconstituted milk) to offset supply shortages in Indian market. There was no quick solution to this growing dependence. Ironically, developed countries, with their legendary efficiencies, had surplus ‘mountains and lakes’ of the stuff posing a disposal problem. Under Dr. Verghese Kurien’s visionary leadership, these two commodities were channeled as gift from them under a program evocatively called ‘Operation Flood’. The sale of reconstituted milks raised resources which were bifurcated into developing local animal husbandry (to raise milk production) and the purchase of the latest and hygienic milk processing machinery made with high grade Stainless Steel from the gifting countries. Farmers’ co-operatives owned milk collection and processing facilities which, through expanding local milk collection and processing, gradually crowded out the imports.

A brief history of milk co-operatives in India: For over a decade after independence, India imported massive tonnages of milk powder and butter oil (milk fat to raise the fat content of reconstituted milk) to offset supply shortages in Indian market. There was no quick solution to this growing dependence. Ironically, developed countries, with their legendary efficiencies, had surplus ‘mountains and lakes’ of the stuff posing a disposal problem. Under Dr. Verghese Kurien’s visionary leadership, these two commodities were channeled as gift from them under a program evocatively called ‘Operation Flood’. The sale of reconstituted milks raised resources which were bifurcated into developing local animal husbandry (to raise milk production) and the purchase of the latest and hygienic milk processing machinery made with high grade Stainless Steel from the gifting countries. Farmers’ co-operatives owned milk collection and processing facilities which, through expanding local milk collection and processing, gradually crowded out the imports.

The need for expanding and spreading milk processing facilities: ‘Operation Flood’ was a stunning success in the hands of committed professionals and India is presently the world’s largest milk producer. Today you buy plain fluid milk in plastic pouches and ‘tetrapack’ bricks round the clock, round the year; in fact the sterile milk in ‘bricks’ has reduced milk to a grocery thing. The mind-boggling variety of milk products on market shelves and this ‘flood’ of milk have also raised the incomes of the farmers. By 2030, a mind-boggling one third of world’s milk is expected to be produced in India – obviously throughout the country. India will need to process all the milk left after distribution of fluid milk, thru processing facilities close to milk production centres. The farmer will enter the market to buy all kinds of goods. The consumer will get to buy a variety of milk products apart from fluid milk any time. Exports will have to increase to mop up surpluses from domestic consumption; government revenue and foreign exchange earnings will boom.

The need for expanding and spreading milk processing facilities: ‘Operation Flood’ was a stunning success in the hands of committed professionals and India is presently the world’s largest milk producer. Today you buy plain fluid milk in plastic pouches and ‘tetrapack’ bricks round the clock, round the year; in fact the sterile milk in ‘bricks’ has reduced milk to a grocery thing. The mind-boggling variety of milk products on market shelves and this ‘flood’ of milk have also raised the incomes of the farmers. By 2030, a mind-boggling one third of world’s milk is expected to be produced in India – obviously throughout the country. India will need to process all the milk left after distribution of fluid milk, thru processing facilities close to milk production centres. The farmer will enter the market to buy all kinds of goods. The consumer will get to buy a variety of milk products apart from fluid milk any time. Exports will have to increase to mop up surpluses from domestic consumption; government revenue and foreign exchange earnings will boom.

Dried milks i.e. condensed milk and milk powder, represent ‘concentrated and contracted’ milk which have the obvious advantage of good keeping quality and high milk-equivalence at low shelf space. That they can be converted to fluid milk is largely irrelevant because of ready availability of fresh fluid milk all the time. Their utility lies in their potential for quick and easy conversion to Indian style sweets – an issue that will soon be given its due detail right here. Their export potential to milk-deficient overseas geographies is obvious.

Dried milks i.e. condensed milk and milk powder, represent ‘concentrated and contracted’ milk which have the obvious advantage of good keeping quality and high milk-equivalence at low shelf space. That they can be converted to fluid milk is largely irrelevant because of ready availability of fresh fluid milk all the time. Their utility lies in their potential for quick and easy conversion to Indian style sweets – an issue that will soon be given its due detail right here. Their export potential to milk-deficient overseas geographies is obvious.

Limited nutrition loss during processing: Fluid milk, flavoured milks, ice-creams, cream, milkshakes, yoghurts, curd, chhachh, lassi, cheese and its processed versions, etc. lose little nutrition because heating is limited and at low temperatures. Shrikhand, paneer and cheese are merely milk getting separated into solid and fluid (whey) parts without much heat application; the latter can be dried to astonishingly nutritive ‘whey powder’. (Butter similarly produces ‘buttermilk’ which has a separate identity). Condensed milk and milk powder require drying by evaporation of water under vacuum at lower temperatures than at home thereby limiting nutrition loss.

Limited nutrition loss during processing: Fluid milk, flavoured milks, ice-creams, cream, milkshakes, yoghurts, curd, chhachh, lassi, cheese and its processed versions, etc. lose little nutrition because heating is limited and at low temperatures. Shrikhand, paneer and cheese are merely milk getting separated into solid and fluid (whey) parts without much heat application; the latter can be dried to astonishingly nutritive ‘whey powder’. (Butter similarly produces ‘buttermilk’ which has a separate identity). Condensed milk and milk powder require drying by evaporation of water under vacuum at lower temperatures than at home thereby limiting nutrition loss.

Whey powder – a winner dairy co-product: ‘Chhachh’ or thin khari lassi is simply churned curd diluted with water. (Salt it minimally; use green as well as dry spices and pulped vegetables like cucumber to increase its appeal.) Whey is the watery, transluscent by-product of separating protein-rich part from milk curdled by some means.

Whey powder – a winner dairy co-product: ‘Chhachh’ or thin khari lassi is simply churned curd diluted with water. (Salt it minimally; use green as well as dry spices and pulped vegetables like cucumber to increase its appeal.) Whey is the watery, transluscent by-product of separating protein-rich part from milk curdled by some means.

The familiar forms of wheys

Maska or chhenna whey as a by-product of shrikhand making: It is the lightly fluorescent yellowish green watery fluid that trickles out when we tie up and hang home-set curd. Industrially, it is separated by centrifugation of churned curd and needs to be allowed to flow out as a part of liquid effluent if not captured for further processing. At home it can stay fresh in a glass bottle in the fridge for days, except for some lightening of colour and souring. We, the people behind this blog, have only now eased up on making shrikhand at home. Until a few years back, its various versions were everyone’s favourite as a pro- and pre-biotic summer dish. We use the separated whey in the following ways:

Maska or chhenna whey as a by-product of shrikhand making: It is the lightly fluorescent yellowish green watery fluid that trickles out when we tie up and hang home-set curd. Industrially, it is separated by centrifugation of churned curd and needs to be allowed to flow out as a part of liquid effluent if not captured for further processing. At home it can stay fresh in a glass bottle in the fridge for days, except for some lightening of colour and souring. We, the people behind this blog, have only now eased up on making shrikhand at home. Until a few years back, its various versions were everyone’s favourite as a pro- and pre-biotic summer dish. We use the separated whey in the following ways:

(i) As a natural hair-conditioner. (ii) As a partial replacement of water for daily chhachh, lassi, smoothies, sherbets, daals, soups, subjis and Gujarati style kadhi.

Never throw it away but use it up in a few days. Note that shrikhand is superior to all the concentrated milk sweet dishes made at home because, far from any loss of nutrition, there is tremendous pro- and pre-biotic value addition.

2.  Cheese whey: There are hundreds of cheese varieties in the world, of which India has taken to the Cheddar (and, to some extent, Mozzarela) variety in a big way. It is an industrial product formed when milk is stirred in special vats with an enzyme when curdled cheese and whey separate out. This curdled ‘fresh’ cheese gets ‘cured’ when stored on racks under controlled atmosphere conditions and is eventually processed into sheets, chiplets and blocks that we buy. Roughly one part of cheese produces nine parts of whey.

Cheese whey: There are hundreds of cheese varieties in the world, of which India has taken to the Cheddar (and, to some extent, Mozzarela) variety in a big way. It is an industrial product formed when milk is stirred in special vats with an enzyme when curdled cheese and whey separate out. This curdled ‘fresh’ cheese gets ‘cured’ when stored on racks under controlled atmosphere conditions and is eventually processed into sheets, chiplets and blocks that we buy. Roughly one part of cheese produces nine parts of whey.

3.  Paneer or cottage cheese whey: It separates from milk that has been ‘chemically curdled’ i.e. acidified with lemon juice or citric acid or vinegar at home and with hydrochloric acid in a plant. Paneer is the targeted product.

Paneer or cottage cheese whey: It separates from milk that has been ‘chemically curdled’ i.e. acidified with lemon juice or citric acid or vinegar at home and with hydrochloric acid in a plant. Paneer is the targeted product.

Interestingly, all wheys are watery with about 5% solids (but it varies) of which about 10 % are proteins. They are extremely interesting byproducts industrially for the following reasons:

- They contain high quality proteins (apart from minerals and vitamins), helpful for muscle development and repair.

- When fresh, chhena and cheese wheys are pro- and pre-biotic i.e. they contain beneficial ‘gut’ bacteria as well as promote their growth in the intestines. Obviously, the bacteria are lost if the whey is heat-processed as in air drying or making kadhi at home. Since paneer is prepared by acidifying milk at a high temperature, it cannot boast pro-biotics.

- They can be formulated directly into value-added fluid energy drinks thru addition of sugar, colouring, flavouring and some strategic fortifying nutrients.

- They can be first concentrated by special ultra-filtration membranes and then dried into ‘whey powders’ by evaporating remaining water. Some loss of nutrients and probiotic bacteria and processing cost would be inevitable.

- If allowed to flow out as a waste product, they would seriously pollute the effluent stream precisely because of those bio-degradable nutrients, raising the cost of its treatment substantially.

This product makes a strong case for itself in large plants where the automatic and free availability of the whey, economy of scale, the excellent realizable market value of the product and the significant reduction in the effluent treatment cost would trump the cost of equipment and processing. Obviously, whey powder production will necessarily be in proportion to the primary cheesy products.

(Next post: Some compelling cases for food processing: Part III, Dried milks)

(Read ‘disclaimer’)

18 thoughts on “Some compelling cases for food processing : Part II, A brief history of milk processing in India and dried dairy wheys”

Hi there, You have done a fantastic job. I will certainly digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they’ll be benefited from this site.

Thank you for your articles. http://www.kayswell.com They are very helpful to me. Can you help me with something?

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you! http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Thank you for writing this post. I like the subject too. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up! http://www.goodartdesign.com

Sustain the excellent work and producing in the group! http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. Please provide more information! http://www.goodartdesign.com

This is really attention-grabbing, You are a very professional blogger. I have joined your rss feed and look forward to in search of more of your great post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information? http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for your articles. They are very helpful to me. May I ask you a question? http://www.kayswell.com

Sustain the excellent work and producing in the group! http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for sharing this article with me. It helped me a lot and I love it. http://www.kayswell.com

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an very long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say great blog!

Thank you for being of assistance to me. I really loved this article. http://www.kayswell.com

I want to thank you for your assistance and this post. It’s been great. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Thank you for being of assistance to me. I really loved this article. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information? http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Thank you for being of assistance to me. I really loved this article. http://www.ifashionstyles.com