Water, food and life, Part I: ‘Jeevan’ in Sanskrit, water has a dark side to it.

We have grown up grasping the many facets of water and air; they are everywhere, life is impossible without them and they are in awe-inspiring abundance. Ironically, they happen to be two of the most abused materials in life with the result that they are getting polluted at an alarming rate. Despite their abundance, many people on this planet don’t get enough water to drink and clean air to breath. Irresponsible wastage and pollution of water and pollution of air are crimes to humanity which will eventually catch up with everyone. ‘Water, water everywhere but not a drop to drink’ may not always remain a cliché’. Time to wake up and make a beginning by understanding the nuances of what all they do for us with the hope that it will initiate some thought and action.

We have grown up grasping the many facets of water and air; they are everywhere, life is impossible without them and they are in awe-inspiring abundance. Ironically, they happen to be two of the most abused materials in life with the result that they are getting polluted at an alarming rate. Despite their abundance, many people on this planet don’t get enough water to drink and clean air to breath. Irresponsible wastage and pollution of water and pollution of air are crimes to humanity which will eventually catch up with everyone. ‘Water, water everywhere but not a drop to drink’ may not always remain a cliché’. Time to wake up and make a beginning by understanding the nuances of what all they do for us with the hope that it will initiate some thought and action.

The ironical double role of water in foods: Insoluble dietary fiber makes smooth and continuous food intake – necessary for sustenance of body’s functioning – possible by facilitating regular excretion of waste from the body. Soluble indigestible fiber further helps in the same function and additionally plays multi-faceted roles enhancing the quality of life. Therefore, they are now considered essential food constituents even if they are non-nutritive. For a more detailed discussion on the role of fiber in our diet, please visit our blogpost: https://letfoodliftlife.com/health-happiness-life-and-food-part-i-what-are-they/. Similarly, water has no direct nutritive function but its life-giving, -sustaining and -saving roles are so multi-faceted, direct and immediate that it deserves an exalted status in our life; ‘jeevan’ is one of its Sanskrit names.

The ironical double role of water in foods: Insoluble dietary fiber makes smooth and continuous food intake – necessary for sustenance of body’s functioning – possible by facilitating regular excretion of waste from the body. Soluble indigestible fiber further helps in the same function and additionally plays multi-faceted roles enhancing the quality of life. Therefore, they are now considered essential food constituents even if they are non-nutritive. For a more detailed discussion on the role of fiber in our diet, please visit our blogpost: https://letfoodliftlife.com/health-happiness-life-and-food-part-i-what-are-they/. Similarly, water has no direct nutritive function but its life-giving, -sustaining and -saving roles are so multi-faceted, direct and immediate that it deserves an exalted status in our life; ‘jeevan’ is one of its Sanskrit names.

- It is a large part of our body and all natural and processed foods.

- Processing of all foods involves water in multiple roles and usually reduces the water content in the finished product.

- Food’s nourishing and protective role within our body is impossible without it.

In one of the basic ironies of life, it has a dark side too;

- It makes foods vulnerable to spoilage in many ways and

- Hepatitis, typhoid, cholera, gastro-enteritis etc. are water-borne diseases, generally affecting the digestive system.

The striking similarities between water and oxygen are one of nature’s wonders; we take up oxygen next.

How water came into existence on the earth – a hypothesis: Though details vary, earth’s origin as the sun’s spin-off, millions of years ago, is a fair model for its birth. Abundance and near-omnipresence of water on the earth deserves a ‘model’ on how that may have happened.

The sun has always been a mind-bogglingly large and hot mass of hydrogen fusing continuously into Helium – matter so distinguished that it has been called fourth state of the matter – ‘plasma’. It is believed that once, millions of years ago, many blobs from this matter exploded away from the sun and started revolving around it. Separated from the actively reacting mass of the sun, one such – the earth – began to cool and a series of complex thermonuclear reactions produced a series of new elements. Some of them reacted among themselves to produce thousands of compounds. At some stage an unthinkably large cloud of water vapour – the product of reaction between hydrogen and oxygen – shrouded the solidifying, irregularly shaped mass of the earth and eventually, it rained for centuries. The mammoth depressions on the now solid earth got filled to create oceans and a serenely beautiful planet was born. Until, eventually, man happened to it.

The sun has always been a mind-bogglingly large and hot mass of hydrogen fusing continuously into Helium – matter so distinguished that it has been called fourth state of the matter – ‘plasma’. It is believed that once, millions of years ago, many blobs from this matter exploded away from the sun and started revolving around it. Separated from the actively reacting mass of the sun, one such – the earth – began to cool and a series of complex thermonuclear reactions produced a series of new elements. Some of them reacted among themselves to produce thousands of compounds. At some stage an unthinkably large cloud of water vapour – the product of reaction between hydrogen and oxygen – shrouded the solidifying, irregularly shaped mass of the earth and eventually, it rained for centuries. The mammoth depressions on the now solid earth got filled to create oceans and a serenely beautiful planet was born. Until, eventually, man happened to it.

Water is everywhere, doing everything!: It is believed that the first simplest (unicellular) life-form was born in water. One of the most fascinating designs of nature is the presence of water (or its vapour) everywhere and this fact has far-reaching implications in all aspects of life. Water is found at depths of thousands of meters below the ground, on the surface and in the atmosphere. That about 70 % 0f earth’s surface is covered with water is widely known. The atmospheric water vapour, being quite clean, can be condensed into liquid potable water in emergencies. Being chemically reactive, water sustains all forms of life, rusts iron, clumps up cement, mushes up bruised fruits and vegetables, helps generate fungal growth on food surfaces, breaks down complex molecules….indeed, water plays some role or the other in almost all natural phenomena.

Water is everywhere, doing everything!: It is believed that the first simplest (unicellular) life-form was born in water. One of the most fascinating designs of nature is the presence of water (or its vapour) everywhere and this fact has far-reaching implications in all aspects of life. Water is found at depths of thousands of meters below the ground, on the surface and in the atmosphere. That about 70 % 0f earth’s surface is covered with water is widely known. The atmospheric water vapour, being quite clean, can be condensed into liquid potable water in emergencies. Being chemically reactive, water sustains all forms of life, rusts iron, clumps up cement, mushes up bruised fruits and vegetables, helps generate fungal growth on food surfaces, breaks down complex molecules….indeed, water plays some role or the other in almost all natural phenomena.

Water in natural life-forms: Our body, as a whole, is 60% water with lungs at 83% and bones at 64%. A male human body contains about 5.5 litre of blood while for females it is 4.5 litres. On an average, over half of human blood is water. Fruits and vegetables contain roughly 80% water with 94% in some tomato and watermelon varieties. Cereals and grains available in the market generally contain about 15% water and the flours, less than that. Water content of milk varies but 85% is a good ball-park. The water content of all natural foods raise a question: how is tomato seemingly solid at about 94% water while a salt solution containing 94% water is entirely liquid?

Water in natural life-forms: Our body, as a whole, is 60% water with lungs at 83% and bones at 64%. A male human body contains about 5.5 litre of blood while for females it is 4.5 litres. On an average, over half of human blood is water. Fruits and vegetables contain roughly 80% water with 94% in some tomato and watermelon varieties. Cereals and grains available in the market generally contain about 15% water and the flours, less than that. Water content of milk varies but 85% is a good ball-park. The water content of all natural foods raise a question: how is tomato seemingly solid at about 94% water while a salt solution containing 94% water is entirely liquid?

Simply speaking, water exists in foods in the ‘bound’ and ‘free’ forms apart from enclosed in sac-like structures. Bound water is attached to the constituents of food, mainly proteins and carbohydrates, thru weak bonds, reducing the ‘activity’ of water. A striking example is the thickening of the slurry of starch or custard powder in water or milk on heating with agitation. With negligible evaporation, water gets trapped between starch macro-molecules to form a thick dispersion of a liquid in water.

Simply speaking, water exists in foods in the ‘bound’ and ‘free’ forms apart from enclosed in sac-like structures. Bound water is attached to the constituents of food, mainly proteins and carbohydrates, thru weak bonds, reducing the ‘activity’ of water. A striking example is the thickening of the slurry of starch or custard powder in water or milk on heating with agitation. With negligible evaporation, water gets trapped between starch macro-molecules to form a thick dispersion of a liquid in water.

Free water is more harmful to the keeping quality of the food; thankfully, it is the first to exit the food while drying. Hence even partially dried foods like sun-dried tomatoes, garlic and onion bulbs, pickles prepared without heat-drying, groundnut kernels, sesame and melon seeds, kokum etc. are quite shelf-stable. Thus, there is no natural food without any water content.

Water in processed foods:

Water and food spoilage: Food downgrades by staling or spoilage. The former happens by water-mediated lumping, air-mediated oxidation, loss of volatiles to atmosphere (including flattening of aerated beverages by leakage of carbon dioxide), spontaneous physicochemical changes (e.g. ‘hardening’ of bread), drying (e.g. shriveling of vegetables) etc. While excessive staling can perhaps be called spoilage, that term is usually reserved for water-mediated growth of microorganisms in foods and the resulting metabolic activity of these micro life forms which distorts the food in several ways. It is easy to see that most staling and spoilage can be arrested simply by isolating the food from oxygen or air and by reducing the ‘activity’ of water in it – central to strategies to limit preservatives in foods.

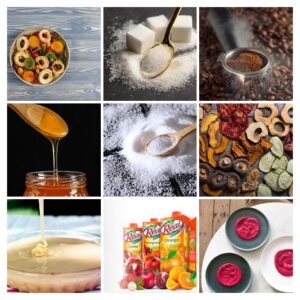

Drying as a preservation technique: It reduces the water in natural foods and produces dehydrated fruits, vegetables, fish and other seafood, juices, coffee, cocoa, spices, sugar, salt etc. The more the water is removed, the more difficult it is to remove more – fact that explains the existence of vegetable and fruit purées, condensed milk, concentrates of aerated beverages, various forms of sugar syrups etc. Such partial drying ensures better ‘rehydration’ to the original form.

Drying as a preservation technique: It reduces the water in natural foods and produces dehydrated fruits, vegetables, fish and other seafood, juices, coffee, cocoa, spices, sugar, salt etc. The more the water is removed, the more difficult it is to remove more – fact that explains the existence of vegetable and fruit purées, condensed milk, concentrates of aerated beverages, various forms of sugar syrups etc. Such partial drying ensures better ‘rehydration’ to the original form.

‘Bone dryness’ is said to have been reached when the moisture content reaches zero %. This, however, is neither possible nor desirable; an excessively dry food (especially a powder) will absorb water from its surroundings to reach an ‘equilibrium moisture content’. The small ‘pillows’ of desiccant powders that you sometimes find in your dry food powders are meant to preferentially soak up the accidental atmospheric water vapor. This saves it from microbial spoilage and helps keep it free flowing; in the former case it is a preservative and, in the latter, an ‘anti-caking’ agent. Sometimes, a permitted anti-caking agent may be intimately mixed with the powdery product itself. It is a good habit to check the labels for the presence of such ‘extras’ that are not always harmless.

How processing usually changes the water profile of foods: The processes of making cheese, butter, jams, preserves, ketchup, bread, biscuits and cookies etc. lead to moisture or water loss. This naturally leads to an improvement in keeping quality though that is not the primary objective. In all cases, a large part of the aforesaid bound water stays with the product. For example, standard bread dough contains about 40% water and, after baking at about 180 deg C for over half an hour, turns into spongy bread loaf with only nominal loss of water. A lot of bound water stays and is even encouraged to stay on to keep the slices supple.

How processing usually changes the water profile of foods: The processes of making cheese, butter, jams, preserves, ketchup, bread, biscuits and cookies etc. lead to moisture or water loss. This naturally leads to an improvement in keeping quality though that is not the primary objective. In all cases, a large part of the aforesaid bound water stays with the product. For example, standard bread dough contains about 40% water and, after baking at about 180 deg C for over half an hour, turns into spongy bread loaf with only nominal loss of water. A lot of bound water stays and is even encouraged to stay on to keep the slices supple.

You never realized that over a third of your favourite bread was water, did you?! Baking lovers have noticed that they cannot bank on baking taking to care of an excessively moist dough; prolonged or high temp baking leads to browning overtaking drying which can’t easily pull out bound water.

You never realized that over a third of your favourite bread was water, did you?! Baking lovers have noticed that they cannot bank on baking taking to care of an excessively moist dough; prolonged or high temp baking leads to browning overtaking drying which can’t easily pull out bound water.

High and low water-contents in foods: Very high water content in solid processed foods is rare; some samples of soy tofu reportedly contain 80 % water, most of it, obviously, bound.

High and low water-contents in foods: Very high water content in solid processed foods is rare; some samples of soy tofu reportedly contain 80 % water, most of it, obviously, bound.

Some food products are born practically water-free; unrefined edible oils are practically dry after simple filtration but that can be attributed to the inherent immiscibility between water and oil. Such dry, filtered oil will remain practically fresh in an opaque, fully filled container for months. Such assurance is not valid in refined soybean oil – also practically free from water – because of its susceptibility to oxidative spoilage. So we add chemical antioxidants to protect it after, ironically, removing some of the natural ones by refining! Point to ponder!!

Some food products are born practically water-free; unrefined edible oils are practically dry after simple filtration but that can be attributed to the inherent immiscibility between water and oil. Such dry, filtered oil will remain practically fresh in an opaque, fully filled container for months. Such assurance is not valid in refined soybean oil – also practically free from water – because of its susceptibility to oxidative spoilage. So we add chemical antioxidants to protect it after, ironically, removing some of the natural ones by refining! Point to ponder!!

Adding water to make a food product is rare; the aerated beverages are famously made by diluting their ‘concentrates’. Milk is reconstituted from milk powder and butter oil (the milk fat) with water but this is merely reversion of earlier dehydration. A similar case is the reconstitution of fruit juices from their powders.

Adding water to make a food product is rare; the aerated beverages are famously made by diluting their ‘concentrates’. Milk is reconstituted from milk powder and butter oil (the milk fat) with water but this is merely reversion of earlier dehydration. A similar case is the reconstitution of fruit juices from their powders.

Retention of water during processing: Interestingly, retention of water (or ‘moistness’) is critical in breads and cakes which become brittle, crumbly and cracked if they lose too much water during baking. This calls for tactful setting of heating time/temperature setting along with use of additives called ‘humectants’ or moisture-retainers. The art and the science of baking is essentially the selection of the composition and the baking conditions. The latter is essentially the arrangement of interplay between the material being baked and heat transferred to it by conduction, convection and radiation, sometimes accompanied by ‘forced convection’ in the form of a fan. Connecting the product of your baking with the baking conditions, the nature of your oven and the composition and the characteristics of your initial ‘baking load’ is the stuff of food science. Yours sincerely, is an avid student.

Retention of water during processing: Interestingly, retention of water (or ‘moistness’) is critical in breads and cakes which become brittle, crumbly and cracked if they lose too much water during baking. This calls for tactful setting of heating time/temperature setting along with use of additives called ‘humectants’ or moisture-retainers. The art and the science of baking is essentially the selection of the composition and the baking conditions. The latter is essentially the arrangement of interplay between the material being baked and heat transferred to it by conduction, convection and radiation, sometimes accompanied by ‘forced convection’ in the form of a fan. Connecting the product of your baking with the baking conditions, the nature of your oven and the composition and the characteristics of your initial ‘baking load’ is the stuff of food science. Yours sincerely, is an avid student.

Next post:

Water, food and life, Part II

The remaining facets of water

(Visit ‘Disclaimer’.)

12 thoughts on “Water, food and life, Part I: ‘Jeevan’ in Sanskrit, water has a dark side to it.”

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something?

Sure. Please post your query here.

You’ve the most impressive websites.

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something?

Thanks for posting. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my problem. It helped me a lot and I hope it will help others too.

I’d like to find out more? I’d love to find out more details.

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you!

What more would you like to know on the topic? Kindly specify here. Also, feel free to browse our blog for more details provided in related posts.

I’d like to find out more? I’d love to find out more details.

Kindly specify your queries here. Also, feel free to browse our blog for more details provided in related posts.

I’m so in love with this. You did a great job!!

The articles you write help me a lot and I like the topic